It is surprising how far a human can go to deny the undesired but evident. All of the discussions about meaning and absurdity by Camus, Sartr, Russel, Becker and the likes are the stubborn denial of the evidence and the obvious. Nevertheless, they go in depths in order to justify their poor choice with complex and rigorous reasoning, which once and for more proves that we are the product of the stories we choose to tell to ourselves. Their stories though sound sublime and heroic wrapped in solemnity in essence are empty. In the words of Andersen’s fairytale punchline, “The emperor has no clothes.”

Category: Thoughts and reflections

What is the measure of success – to have or to be

I still haven’t met a single person, who consciously has made a decision to be a failure, not a single person has made a plan from his childhood to be a loser. It is natural to strive, fight, aim and rush towards a goal. Even the most broken people in our society, when asked about his dreams can produce a single dignified and worthy objective he/she wanted to be and to achieve. We all want to be successful, to be fruitful, to live an abundant and exciting life. However, when asked about success and that desired life, we often get lost in the definitions. What is measure of success then?

Admittedly, we live in the times when the measure of success is very messed up. The social media, educational institutions, marketing and advertisements portray success in a very mercantile manner. The materialistic, possessive mode of existence dominating the modern society expressed in a condensed ‘Career-Stuff&Travel’ model lays at the foundation of the success assessment. This mindset prioritizes acquisition and consumption over the more meaningful way of living. Yet, due to its immediate visibility, ‘Career-Stuff&Travel’ has undeniable argumentative power – you either have it or not. If you have it, show it; if you don’t – shush! Any attempt to challenge the status quo meets the opposition commonly expressed as: “You say so because you are poor” or “Oh, if you are so smart, why are you so poor?”

Two centuries ago Talleyrand, French statesman, has given rather exhaustive and concise argumentation against the absurdity of the claim. He said:

To make a lot of money, you do not have to be smart, but need to lack conscience (Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord).

However, the sense of superiority and self-justification are too hard to set aside. The strong mythology of materialistic success as expression of the inner riches appeals to the deepest needs of a human soul blinding one’s mind with its charm just as it was with the King Theoden from ‘The Lord of the Rings’ under the spell of Grima.

Continue reading “What is the measure of success – to have or to be”

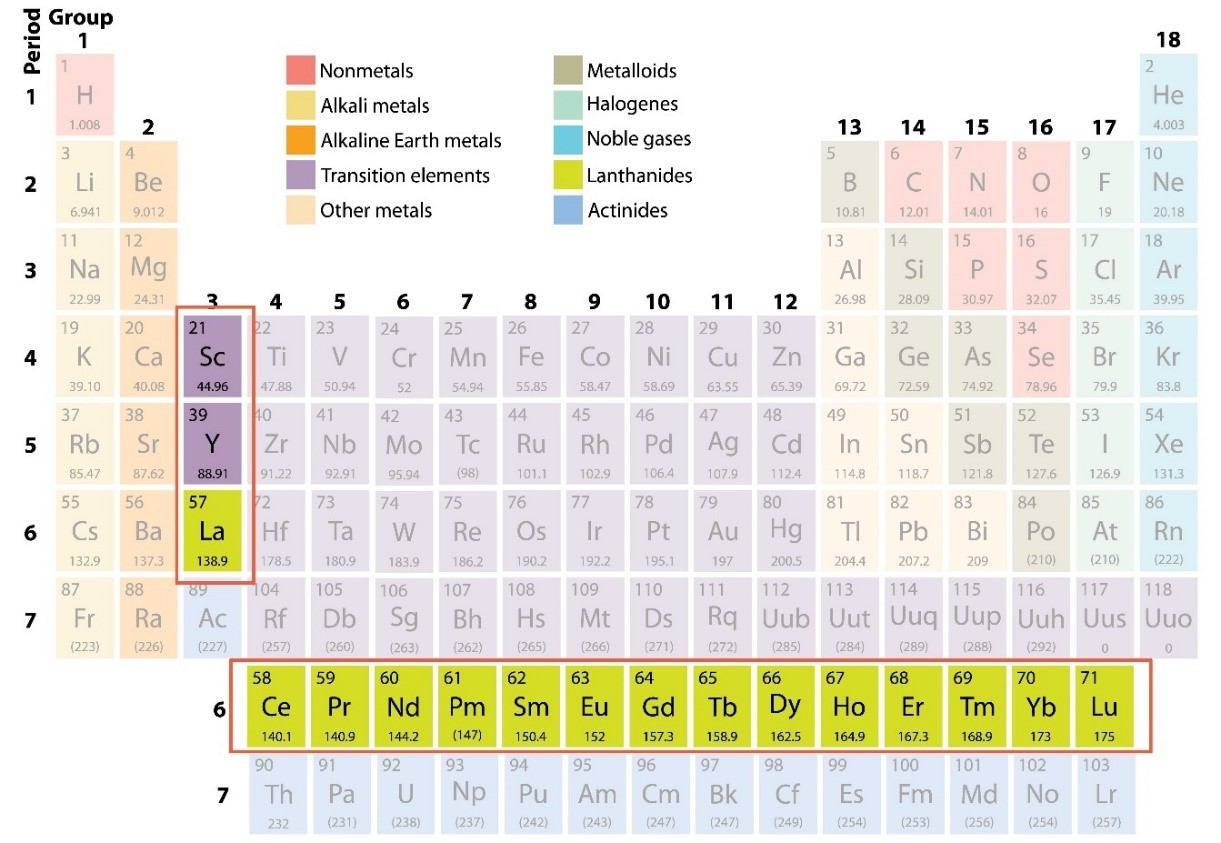

On Trends Related to Recovery of Rare Earth Metals from the Waste of Electronic Devices

Individual Project Work about the prospects of recovering the Rare Earth Metals from e-Waste – On Trends Related to Recovery of REMs from the Electronic Devices’ Scrap (PDF)

What is winning?

On the Danger of Habit

The life of a philistine is as prosaic as the life of the sheep from the old Georgian parable:

“the sheep spent its whole life fearing wolves, but in the end, it was the shepherd who ate it.”

Often, danger does not come from circumstances beyond one’s control, nor from people who pose an obvious threat, but from those who constitute the ordinary course of life and, due to their familiarity, are perceived as normal, as natural.

Who is the shepherd in this proverb?

The shepherd is the one who “feeds”, who influences daily routines, who defines the world and one’s perception of it. With their care and boundaries, they protect but also limit possibilities. Perhaps in the wild, such a sheep would not live long, but how different its life would certainly be compared to the routine of “field-pasture-field.” Would the sheep be as “useful” in freedom as it is within the confines of the flock? That is an interesting question, worthy of an answer. And something tells me that the answer depends on the perspective from which it is given—that of the shepherd, the sheep, or the wolf.

Do other people irritate you?

“For every person, their neighbor is a mirror from which their own vices look back at them. But a person acts like a dog that barks at the mirror, thinking it sees not itself but another dog.” — Arthur Schopenhauer

«Для каждого человека ближний — зеркало, из которого смотрят нанего его собственные пороки. Но человек поступает при этом как собака, которая лает на зеркало, предполагая, что видит там не себя, а другую собаку». А. Шопенгауэр

Aut viam inveniam, aut faciam

Aut viam inveniam, aut faciam

Или найду дорогу, или проложу ее сам.

I will either find a way or make one

Globalisation no more… what is next?

Image source: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201907/01/WS5d196537a3103dbf1432b248.html

Mark my words, but the situation we have today (as of May 2020) in the economy and politics globally is the end of globalisation as we know it. If you missed somehow in the notion of globalisation, it is, according to IMF 2000 definition, “the increasing integration of economies around the world, particularly through trade and financial flows.” Besides the trade and capital movement, it relates among many others to the movement of people and the spread of knowledge/technology as some of the most important mechanisms for the existence of globalisation. We are about to witness how all of these are going to be trashed or replaced. Replaced with what? Now, this is a good question. To even distantly approach it, we need to see why/what for globalisation exists, what happens now (past years, even a decade) to threaten its existence. Only then we can imagine/fantasise what is next.

Why globalisation exists?

It is almost a common sense that trade is a part of the big geopolitical game and the rules were set to serve the interests of the main beneficiary (-ies). Let me reemphasise: it was assembled by the interested player(s) for the expected benefits of the interested player(s). If someone is good at swimming, it would be naïve to propose to compete at marathon running especially with professional runners. If you are good at swimming, then make everyone swim. The existing global trade system was designed to facilitate trade in those areas, where the western civilisation has a relatively good edge against the rest. The system is designed to support the trade of high-tech products, goods and services, and financial instruments which yield thicker profit margins. The rest of manufacturing, for instance, is considered insignificant and was outsourced to the second and third world countries. No one designed the system for the resistance of the heavy stress conditions, global crisis, major threats as this is not the main strength of the one who sets the rules.

In the post-Soviet era/post-Cold War era, it was considered that the development of the globalisation would secure the leading position of the USA as the main beneficiary. The foreign policy of Ronald Raegan administration brought “the giant” to the knees. The decision was made to ransack the Soviet Union, Russia and the satellite states, benefiting of the abundant resources and relatively unsaturated market of Eastern Europe. Think for a moment about the geographic spread: from Eastern Germany on the west, to Yugoslavia on the south, up to Estonia and all the way to Russian Kamchatka laid the market to consume the manufactured products and resources awaiting for someone to get hold of them. The pie was too big to digest alone so the States brought to the table its Western European allies. At about the same time, China was allowed to get access to the globalisation system. China, at the time, was a huge pool of cheap human resource and outsourcing some of the insignificant tasks made good sense. Then producing more advanced products made equally good sense, since no one expected anything of China. The players made money out of this cooperation, but no one expected that China can win the race. The race was for the white gentlemen to win – not for China. Fast forward to present days, here we are: China is the biggest manufacturer, biggest economy, with the biggest internal market, projecting its influence there, where only the gentlemen were allowed (Africa, Middle East, Europe and even Americas).

What happens now?

Difference between Invention and Optimization

Recently, I was a part of Systematic Creativity and TRIZ Basics online class presented by professor Leonid Chechurin from LUT. One of the first questions in the class was to give our own definition of the difference between the invention and optimization. I found it quite interesting especially given the fact that I never thought of that. The result of my reflections are below.

Optimization – gradual change of an existing system, process or solution by upgrading or downgrading existing properties to a new optimum or, in other words, to a new expected outcome. Thus, optimization is the process of reaching a new optimum or a new balance of interests.

Invention is the process of reaching another level of novelty. Invention is a gradual or radical change of the existing solution by adding, upgrading or downgrading the existing properties until a new nonexistent level of problem resolution is found. Novelty is the distinguishing factor between these two.

These processes are different, thus, call for different mindset, expected result and tools.

What would you say about this definitions? How do you define optimization and invention?

Halo effect: difference between reports and stories

This is a part of quotes and thoughts that attracted my attention, while reading the “The Halo Effect …and the Eight Other Business Delusions that Deceive Managers” by Phil Rosenzweig (Free Press, 2014).

pages 15-16:

It’s useful to make the distinction between reports and stories. A report is above all responsible for providing the facts, without manipulation or interpretation. If the accounts about Lego and WH Smith are meant to be reports – which presumably they are, since they’re written by reporters – then words like stray or drift are problematic. Stories, on the other hand, are a way that people try to make sense of their lives and their experiences in the world. The test of a good story isn’t its responsibility to the facts as much as its ability to provide a satisfying explanation of events. As stories, the news accounts about Lego and WH Smith work just fine. In a few paragraphs, the reader learns of the problem (sales and profits are down), gets a plausible explanation (the company lost its direction), and learns a lesson (don’t stray, focus on the core). There’s a neat end with a clean resolution. No threads are left hanging. Readers go away satisfied.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with stories, provided we understand that’s what we have before us. More insidious, however, are stories that are dressed up to look like science. They take the form of science and claim to have the authority of science, but they miss the real rigor and logic of science. They’re better described as pseudo-science.