PDF version: Diduc Alexandru – Political Economy, Moldova

Alexandru Diduc

April 22, 2008

Moldova – Natural Tragedy or Controlled Disaster

4052 words

Abstract

This essay will focus on the reason for the instability in Moldovan economy and the failing state the Republic of Moldova is. The central idea of the paper is that the causes for the controlled disaster in the country are not only internal but mostly they are of the external origin. The internal causes are the mostly agrarian economy and the transnistrian conflict. The external causes are the incompatible geopolitical and geo-economical interest of the EU and Russia. Transnistrian region and Moldova is used in this game as a small change and a tool of control. The change in the wellbeing of the united Moldova is expected to come with the settlement of the conflict and dynamic implementations of reforms.

—

Introduction

Moldova is widely famous for its wines, its poverty and 4,163 km² of uncontrolled territory on the left bank of the Dniester River. It is a matter of fact that Moldova is a failed state and a weak functioning economy. These are just consequences of the more complicated processes that influence the outcome. The Republic of Moldova (RM) is just a small card played on the table in the geopolitical game of the superpowers in the region. Unmatched geopolitical and geo-economic interests of pragmatic and contradicting Russia and EU and of ambitious Moldova are the main reason for the failed state and poor economy as Moldova is now. But the change is expected to come in 2009 and the following years with the settlement of the Transnistrian conflict and the energetic implementation of the reforms.

My assumption is that there are no any inner parties interested in fueling the instability in the state between Moldova and Transnistria, and which stand behind the weak economy. Thus, there should be any external forces, Russia and EU, which directly or indirectly influence the present situation in the economy and state. Moldova is a peaceful nation and the nation that highly values stability, predictability and wealth. Moldovan people like to work and enjoy the times of economic and political stability more than anything else. Moldovans have low but firm expectations of stability, which they pursue either through the migration or short term employment abroad. But mostly these are the short-term solutions and in the good times the population is going to return. Thus, the resolution of the Transnistrian conflict and dynamic economic reforms along with the EU integration will bring the prosperity and positive change in this region.

Country’s profile – insignificant economy and failed state

There is nothing new in the fact that Moldovan economy is weak and functioning poorly, and the state is failed. And this situation remains unchanged since the independence of the RM. The country’s account reveals interesting insights in the reason for that. Moldova remains the poorest country in Europe. It is landlocked, bounded by Ukraine and Romania. It is the second smallest country of the former Soviet republics and the most densely populated. On average, industry accounts for less than 15% of its labor force, while agriculture’s share is more than 40%. As, for example, “in 1997, around 43% of the net material product of Moldova (excluding Transnistria) was based on agriculture. This sector employed more than 35% of the labor force. In the same year, agriculture and the food-processing industries together accounted for around 75% of the country’s exports” (Hill, 2000). In 2005, 40.7% of labor force is involved in agriculture, 12.1% in industry and 47.2% in service sector. (World Factbook, 2008).

Moldova’s mild and sunny climate is explained by the proximity to the Black Sea. This makes the area ideal for agriculture and food processing, which accounts for one third of the country’s GDP. The fertile soil supports wheat, corn, barley, tobacco, sugar beets, and soybeans. Beef and dairy cattle are raised. Pork meat production is also significant to the region. Beekeeping is widespread. Moldova’s best-known product comes from its extensive and well-developed vineyards. In addition to world-class wine, Moldova produces liqueurs and champagne (Hill, 2000). It is also known for its sunflower seeds, walnuts, apples, and other fruits. The important fact is that there is not much heavy industry or manufacturing in Moldova. In fact, the 80% of manufacturing can be found in Transnistria. “Light industry, including the assembly of tractors and washing machines, food-processing, footwear, textiles, and clothing industries were developed, as well as energy production and some heavy engineering in the region based on the city of Tiraspol (Hill, 2000).”

The economic crisis caused by the transition from command to the market economy in Moldova was deeper and lasted longer than in most countries of Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Among the major factors which intensified the crisis were the orientation toward agricultural production, a shortage of raw materials and lack of own energy resources, small capacity of the domestic market, and internal political conflict in the eastern regions of the country (Lupu, 2005).

The Failed State Index 2007 (FSI, 2007) ranks Moldova on the 48 place, with a score of 85.7 out of 120, being on “the borderline” of failing. The internal conflict in Transnistria is the main reason of instability; other issues (economic instability, external intervention, deligitimization of state, epidemic size of human flight accounting for 25% of population (MIS, 2005)) are the outcomes of this conflict. It is caused by, officially (USDS, 2005), the ethnic conflict of Slavic-Moldovans (right bank of Dniester) and Romanian-Moldovans (left bank) finds poor confirmation in the FSI (4.7). Unofficially, this is the political instability designed to serve the geopolitical interests of Russia (Pop, Pascariu, Anglitoiu, Purcarus, 2005). Thus, mostly agrarian and subjected to the “internal” conflict, Moldova has insignificant political, economic or military power to bargain in any discussion about the conflict resolution. It makes the country’s fate vulnerable to the external manipulations of “the big brother.”

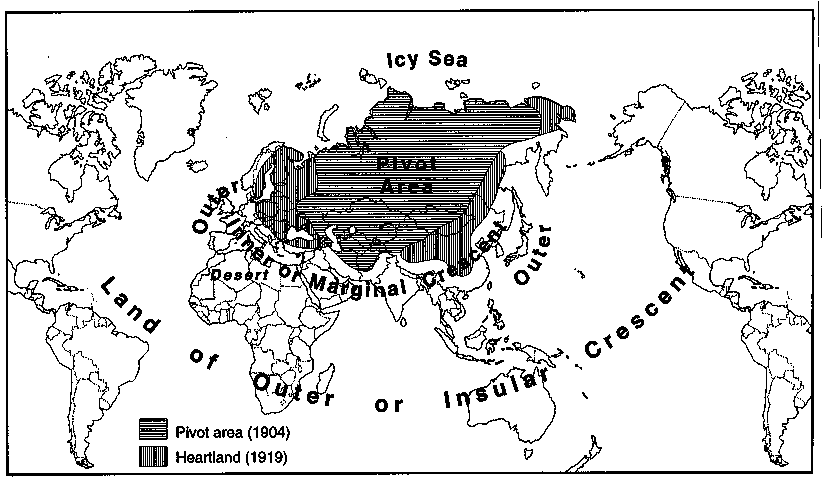

In the middle of nineteenth century appeared a theory that explained the political-military power structure in the world. It assigned paramount importance to Central Asia, the high seas, and Eurasia – the Heartland theory (Evans & Newman, 1990). This area’s significance is determined by the coupled splendid isolation by mountains and deserts and with vast space and resources. It composes a defensible base from which to project crucial power (Schlesinger, 1973). The postulates of the theory are following: “Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland. Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island (Eurasia). Who rules the World-Island commands the world (Schlesinger, 1973).” Recently the Hearland area was reconsidered to be the Caucasus, Central Asia, Afghanistan and the enlarged Middle East (see the Figure 1 below) (Sava, 2004). Zbigniew Brzezinski calls this area the new “Global Balkans”, – “the most volatile and dangerous region of the world”. This region has “the explosive potential to plunge the world into chaos (2004).” The value of the “Global Balkans” is not only in the destabilizing potential, but in the wide energy resources too. The 61 percent of the oil reserves and 41 percent of gas ones are found in this region (Brzezinski, 2004).

The Black Sea area in this context is something more than the westerner’s gateway to the Heartland. This area provides the significant amount of the energy resources to the EU’s states, and the demand to which is expected to grow (Pop, et. al, 2005). The demand will be covered through the pipelines extended to the energy resources in the Caspian Sea and the Near and Middle East. These resources have to minimize the EU’s dependency on Russian gas (Sarchinschi & Buhnareanu, 2005). In its turn, Russia is also interested in the strengthening of its interest in the region. Putin constantly saying that “the Azov-Black Sea basin is in Russia’s zone of strategic interests” and that “the Black Sea provides Russia with direct access to the most important global transport routes, including economic ones (Johnson, 2003).” Russia is preparing the “gas OPEC,” which is going to include the countries Algeria, Bolivia, Brunei, Venezuela, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Katar, Libya, Malaysia, Nigeria, UAE, Oman, Trinidad, Tobago and Equatorial Guinea (Кисилев, 2008). A good part of these countries are not EU and NATO friendly. So this future organization is also intended to control the prices on gas around the world.

In this big game, Moldova is a small change as it can be easily seen from the external policies of both parties. Moldova is a “buffer state” between two major geopolitical players: the Euro-Atlantic one (EU and NATO) and the Euro-Asian one (under the Russia’s tutelage). When the Soviet Union collapsed, lots of states started to look to the West and the EU accession. When the Baltic States, Poland, Romania joined the NATO, Russia was isolated in the west by the “sanitary belt.” It is expected to be totally closed once Ukraine will join the NATO (Pop, 2005). As a matter of fact, Moldova does not represent that much economic value for both parties as much as political one. The main interest in the area is Ukraine especially in the light of the westerner’s aspirations about the country and the bright future as a part of NATO and the EU (USDS, 2004). Territorially fragmented Moldova is not an interesting area for the EU’s investments, because of the insecurity of the political vector the country will follow. For Russia, development of the lasting relationship with the RM is not interesting too. This became clear after the summit in Yalta on 18-19 September 2003. During this summit the presidents of the Russian Federation, Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan signed an agreement on the establishment of a Common Economic Space (CES). CES was supposed to become a copy of the EU. This agreement has touched such areas as “joint taxes, free circulation of goods, services, capitals and workforce, as well as the commercial legislation harmonization in order to remove the border barriers (Pop et al., 2005).” Chisinau was excluded from this arrangement. The three counties, except Belarus, were the main industrial drive of the Soviet Union. In this case Belarus is a “buffer state,” as Moldova is, but its strategic location is more important than Moldova’s one especially due to the NATO’s enlargement in the Baltic area. The fact that Moldova was not included in CES proves that it has no economic potential for Euro-Asian Union. More than this, it could be a burden too. The exclusion from the CES produced Vladimir Voronin’s protests who said the RM will subsequently take more decisive actions targeting the European Union (Pop et al, 2005). Another crucial event took place on 24 November 2003, when Chisinau rejected the Russian plan (Kozak Plan) to solve the Transnistrian conflict. Rejecting Kremlin, Moldova had no other way to go but to the rapprochement towards the EU.

But politically Moldova is very significant to Russia, which explains the Russia’s constant attitude towards Tiraspol. Russia in fact is frankly declaring that it has its own interests in Transnistria (Nantoi, 2008). The significance of Transnistria to Russia is not its Russian-speaking population, but in the fact that with the help of Transnistria, Moscow “can keep the

Republic of Moldova under its tutelage, Ukraine under control and the Balkans under surveillance (Pop, et al., 2005).” That is why Russia will continue to play the Transnistrian card, in its efforts to slow down the crisis regulation on a definite period of time. It will force the RM to remain prisoner in “a grey area under Russian influence (Pop et al., 2005).”

The Prisoner of Its Own Fate

Moldova’s strategic location is the cause of the constant enmity of the geopolitical interests. On the one hand, Brussels is interested in the peaceful and united Moldova in order to secure the supply of the energy resources and secure the NATO expansion. But currently the EU does not want to invest in the instable country that is in the crisis of its vector of interest. On the other hand, Moscow is interested in the pent in of the NATO expansion and preservation of its economical interests in Transnistria. In this context, Moldova plays the role of the prisoner of its own fate. Chisinau depends on Moscow economically and politically, and attracts insufficient attention from the EU, although the country is drawing its future as a part of the EU.

Moldova is highly dependent on the energy resources from Russia since there are none on the territory of the state and on the exports to Russia as well. Russia and Ukraine satisfies 97% of Moldova’s energy demand. This fact places Moldova in a vulnerable and highly dependent position from Moscow (Serebrian, 2004). At the same time, Moldovan trade is highly oriented towards the Russian market. As in the 2005, 35% of Moldova’s exports were directed to Russia (Statistica, 2007). The dependency was later used as a tool to discipline the country for the “unfriendly” attitude towards Transnistria with the wine ban, which was 80% oriented towards Russia, and the raise in the gas price (Kennedy, 2007). The reorientation of the markets will significantly reduce Moldova’s vulnerability from Moscow’s decisions.

Transnistrian conflict reveals the political dependency on Russia Foreign Policy. When it became obvious that USSR was going to collapse, there rose nationalist movements and aspirations of Moldova’s reunification with Romania in the 1989. A 1989 law, which made Moldovan an official language, added to the tension between the two banks. Trans-Dniester proclaimed its secession in September 1990 (BBC, 2008). Unable to reach the consensus over keeping Transnistria as part of Moldova, the parties fought the 1991-1992 war. The 14th Russian Army secured the victory to Transnistria. A ceasefire was signed in July 1992, and a 10-km demilitarized security zone was established (BBC, 2008). Until the present day Russia did not explain why its forces were involved in the conflict. It is worth noticing that the 40 000 tons of the armament, which was retrieved after the collapse of the Berlin Wall from the Balkans and the Eastern Europe, was brought to Transnistria and was stocked in Colbasna. This armament is stocked under the blue sky and has the potential of the explosion in every moment. According to Moldovan military, the consequences of the explosion can be as of the Hiroshima bomb, wiping out everything in the range from 500 to 3000 square kilometers. It can influence not only Moldova, but Ukraine and Romania too (ISSS/ISAC, 2006). The huge armament stock was a reasonable cause to defend the region with the use of the 14th Army. The transnistrian conflict, thus, has the purpose of control of this territory. Transnistria and other frozen conflicts, such as the one in Abkhazia, Adjaria, South Ossetia and Nagornyi-Karabach are intended to keep the actual countries and the neighbors (ex. Moldova and Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia) under the control of Moscow and to stop the expansion political, economical and military presence of the West in the close proximity to Russia (Pop, et al., 2005). Meanwhile Moldova expresses strong will to build the future as a part of the EU.

The EU is having a skeptical attitude towards Moldova’s interests. Moldova is blamed for having not expressed the clear attitude towards the integration. These critiques are built on the fact that the country is still a part of CIS although it is lacking the future (Political, 2005). The Moldova’s rhetoric about the will to strengthen the state through the participation in the CIS and the EU (Frunatasu, 2002) makes Brussels become cautious about the intentions and interests of the RM (Pop et al., 2005). In this light, the political orientation of Vladimir Voronin, the re-elected president of the RM, makes the trust even more vulnerable, although the EU is maintaining the optimistic opinion. The first election of Voronin happened on the platform of support of the accession of Russia-Belarus Union. The reelection happened on the orientation to the EU. The change in the orientation was determined by the political survival of the communist leader (Pop, et al, 2005). That raises the questions about his good will to proceed with the EU integration. This becomes an issue in the light of the pragmatic politics of Voronin expressed in the motto “we must be where it is convenient for us to be (Pop et al, 2005).”

In fact, Moldova can not change anything on its own, leaving the decision to be reached on the level of Russia – EU. Without Transnistria or as a fragmented state, Moldova is not interesting for the EU; on the other hand, united Moldova as a part of the NATO represents low interest for Russia since it loses its stronghold and positions. Moldova, thus, is experiencing quite delicate situation. In order to set the conflict in Transnistria, Moldova has to vow fidelity to Russia, especially when the country has nothing else to offer, and keep the vow as long as Russia wants. On the other hand, in order to become a part of the EU, the same vow has to be given to Brussels and no pro-Russian direction will be welcomed. Moldova got stuck in its dilemma, which can explain the rhetoric of the president. Voronin is in a bad grace of Russia after the failure to sign the Kozak Plan in 2003. Being prisoner of his pro-European rhetoric, which built a high expectation in the society, along with the political self-preservation can guarantee that the western orientation will be the main vector of interests of Chisinau. Meanwhile, Russian intervention in the political life of the country will remain the major factor of instability even after the settlement of the transnistrian conflict. The peaceful settlement is highly desired by Moldovan president now, one year from the Parliament election in Moldova.

What dreams may come

Parliament’s election of 2009 is making the 2008-2009 periods very significant for the political elite of the RM. This is a last chance, that communists have, to prove that they fulfilled the promises from the previous election – the EU integration, the settlement of the transnistrian conflict. That is why this period is also expected to be full of promises and exciting PR news. At the same time, this can be a period for a lot of change to come in both political and economic sphere. The communist actions will determine the result and the results will determine the communist political future.

Recently there were made attempts to reestablish the conversation over the settle of the conflict. The presidents of both republics had a meeting after the 7 years of break (Today, 2008). There where discussed the basic step to development of the trust between the two banks. The parties expressed their expectations from each other and came up with the suggestions about the settlement of the conflict. Moldovan government is very optimistic about the resolution of the conflict and is expecting to settle it till the end of the year (Minister Stratan, 2008). Meanwhile, scholars express skepticism about the settlement of the conflict, unless the interests of Russia are not secured in the region, which may take a long time for Moldova to concede it (Firm Reconcile, 2008). The fact is that the solution may come from Moscow, when it will be ensured that the 90-100 percent of an influence over Tiraspol is worth trading of on the smaller percent of influence in the reunited Moldova (Wagstyl, 2007). The settlement of the conflict is depending on two factors. First factor is the scale of the precedent of proclamation of Kosovo’s independence. Second, on whether the Ukraine will become a part of Membership Action Plan with the future of accession to NATO. This will hurt Russia’s interests and Transnistria, thus, will be the last stronghold of Russia, which it will surely like to keep, destabilizing the region (Firm reconcile, 2008). This year will reveal the real interests of Moldova although the administration is shouting out loud about the European integration as a first priority (President Voronin, 2008).

Political instability, on the other hand, provides no excuse for the slow implementation of the economic reforms. When in 2006 Moldova raised the question of the membership in the EU, the Brussels’ officials derided it saying that these are “premature (Lobjakas, 2006).” Indeed, though there were done important reforms in the economic, political and structural reforms, price liberalization, small-scale privatization and trade ease are insufficient evidence that Moldova’s economy and state are ready to join the EU. Meanwhile, the officials said that these reforms could secure the access to the EU market as a part of “GSP Plus” (EU equivalent of most-favored nations), where all the non-agricultural goods can freely access the EU market with the condition of proper representation of origin and the proper quality certification (Lobjakas, 2006). The EU told Moldova to not to concentrate on the membership with the union and possible benefits from that, but to focus on the essential reforms. Moldova has to look for changes in the area of “human rights, corruption reduction and cross-border crimes, minority protection and the rule of law (Lobjakas, 2006).” Together with said above the following process of trade liberalization and reduction of government control over the markets may bring positive change and the warming in the relations with EU and draw closer to the ideals of free market.

Three years later Moldovan Minister of Foreign Affaires and European integration claims again that Moldova is ready to go further and sign a new political document. The arguments are that the conditions of the Action Plan were over-fulfilled. Moldova improved more than two hundred laws, entered the regime of additional autonomous trade preferences with the European Union (GSP+), opened the EU Visa Application Center in Chisinau, and resolved many other problems (Andrei Stratan, 2008).

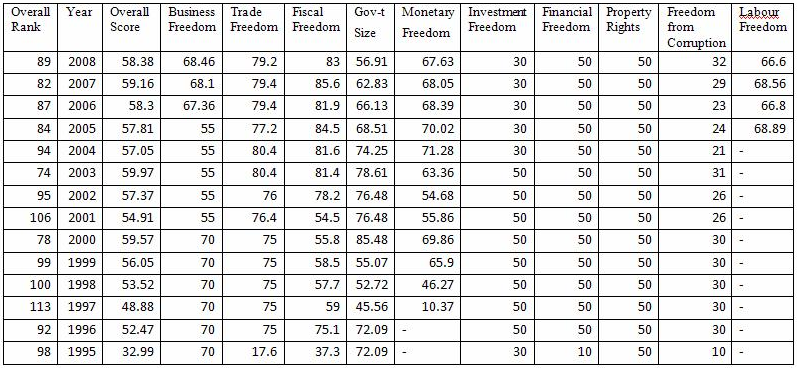

But such economic indicators as Transition Indicator by EBRD, Index of Economic Freedom (IEF) and Doing Business reveal that the change is insignificant. Analysis of the IEF 1995-2008 gives the significant insights in the economy. The overall score of Moldovan economy is balancing between 50 and 60 with the passage of time. That proves that Moldova’s progress in implementation of the reforms does not compete with the other developing countries in the region. The scores in the table show that Moldova is developing some aspects of the economy and other important aspects do not receive an appropriate attention. As for example, the investment freedom (30 out of 100), financial freedom (50), freedom from corruption (32) and government size (56.91) requires strategic reorganization (IEF, 2008). These aspects are the spheres were the attention should be paid without interfering with the reforms in other spheres. The reason for the slow pace of implementations of reforms can be the bureaucracy (government size – 56.91).

The IEF and other indicators provide the explanation to why the EU urges Moldova to implement the “well-thought economic and political reforms (Solana, 2008).” It promises to be a partner in this process but everything will depend on Chisinau. Javier Solana, the EU Foreign & Security Policy Chief and Secretary General of the European Union Council, stressed that the implementation of the reforms can serve as a basis to the Transnistrian conflict resolution (Solana, 2008). Meanwhile, the US lawmakers proposed to forgive Moldova’s foreign debt. The forgiveness of debt was not unconditioned. It came along with the high responsibilities, which the country has to follow including “the transparent and effective budget processes, no support for terrorism, cooperation in international counter-narcotic efforts, and uphold human rights standards, the Voice of America informs (US House, 2008).” In addition, available funds as a result of loan forgiveness must be used for anti-poverty programs, and governments would have to publish annual reports on how money is spent (US House, 2008). These conditions serve as the prerequisite to the development of the RM as well as the tools of making the country loyal to the westerners and securing their interests in the region. Moldovan government on the other hand is promising to maintain a high level of reform to meet the EU strict conditions (Moldova to, 2008). Thus, the coming two years will be highly important for the communist administration to prove again that they are worth the EU trust and the trust of the population of the country on the both sides.

Conclusion

Moldova is a small country in the South-East Europe with weak economy and all infamous attributes of the failed. The main reason for such ineffable description is the strife for the power and dominance in the region between two superpowers – Russia and the EU. Transnistrian conflict, weak and dependent economy controlled by Russia and left alone by the EU only magnifies the disaster the country. Powerless and politically insignificant the country is left on the fate’s choice which lies in the hands outside the country. The coming year is thought to have a significant role in the fate of the country and the future will be determined by the direction the country will choose – either peace and economical prosperity in the future or the deeper disaster the country is already experiencing. The preconditions for peace and prosperity are already in place. The single thing that Moldovan government has to do is to use the opportunity to the full.

—

References

Возможно ли прочное урегилирование конфликта в 2008 году? [Firm reconciliation of the conflict – Is it possible in 2008?] (08 April 2008). Retrieved April 22, 2008 from: http://ava.md/material/559.html

Сегодня в Бендерах состоялась встреча Воронина и Смирнова [Today there was a meeting in Bender of Voronin and Smirnov]. (April 11, 2008). All Moldova. Retrieved April 22, 2008 from: http://politicom.moldova.org/stiri/rus/111300/

Andrei Stratan says Moldova has advanced substantially on its path to Europe… (April 10, 2008). Moldova Azi. Retrieved April http://www.azi.md/news?ID=48908

Brzezinski, Zbigniew. (Winter 2003/2004). Hegemonic Quicksand. The National Interest, p. 5. Retrieved April 22, 2008, from http://www.kas.de/upload/dokumente/brzezinski.pdf

Comert exterior. (1997-2007) Biroul national de Statistica al Republicii Moldova. Retrieved April 22, 2008, from http://www.statistica.md/statistics/dat/1126/ro/Comert_exterior_1997_2007_ro.pdf

Country Resource – Moldova. Migration information source (MIS) 2005. Retrieved April 22, 2008 from: http://www.migrationinformation.org/resources/moldova.cfm

Fruntasu, Iulian. (2002). O istorie etnopolitica a Basarabiei (1812-2002) An Ethno-political history of Bessarabia, 1812-2002. Cartier, Chisinau, p. 405.

Hill, R.J. (2000). Moldova. In P. Heenan, M. Lamontagne (Ed.), The Russia & Commonwealth of Independent States Handbook (112-122). Chicago and London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publisher.

Johnson D. (September 18, 2003). Russia, Ukraine devide Sea of Azov. CDI Russia Weekly. Retrieved April 22, 2008, from http://www.cdi.org/russia/274-18.cfm

Kennedy, Ryan. (April 4, 2007). Moldova: Counting Losses As Russian Wine Ban Lingers. Retrieved April 22, 2008, from http://www.rferl.org/featuresarticle/2007/04/AF0610F8-0D72-4EB7-BFC0-008BC39328DE.html

Kiseleva, A. (April 21, 2008). Россия готовит «газовую ОПЕК», [Russia prepares the “gas OPEC]. Retrieved April 22, 2008, from http://www.vz.ru/economy/2008/4/21/161448.html

Lobjakas, A. (2006). Moldova: EU Officials Say Union Membership Hopes Are Premature. Retrieved from Radio Free Europe/Radio free web site: http://www.rferl.org/ featuresarticle/2006/04/40898395-58a4-4eec-ae39-6d468f8b909b.html

MacKinder, J.H. (1904). The Geographical Pivot of History. Geographical Journal XXIII Graham Evans and Jeffrey Newnham. The Dictionary of World Politics (Hemel Hempstead, 1990).

Minister Stratan confident Transnistrian conflict will be solved till end of year. (April 18 2008). Moldova Azi. Retrieved April 22, 2008 from: http://www.azi.md/news?ID=49018

Nantoi O. (January 28, 2008).Year 2007: Transnistrian issue. Retrieved April 22, 2008, from http://www.azi.md/comment?ID=47885

Political & Security Statewatch. (May-June, 2005). Monthly Bulletin on Moldova Idis Viitorul, no. 3,p.5.

Pop, A., Pascariu G, Anglitoiu G, Purcaru A. (2005). Romania and the Republic of Moldova – Between the European Neighborhood Policy and the Prospects of EU Enlargement. European Institute of Romania. Retrieved April 22, 2008 from: http://www.ier.ro/PAIS/PAIS3/EN/St.5_EN_final.PDF

President Voronin sets priorities for 2008. (April 21, 2008). Moldova Azi. Retrieved April 22, 2008 from: http://www.azi.md/news?ID=49036

Sarcinschi, A., & Bahnareanu, C. (2005). Redimensionari si configurari ale mediului de securitate regional – zona Marii Negre si Balcani, [Changes and configuration of the regional security environment – the area of the Black Sea and the Balkans]. Publishing House of the National Defense University, Bucharest, p. 18.

Sava, Ionel Nicu. (June 16, 2004). Geopolitical Patterns of Euro-Atlanticism. A Perspective from South Eastern Europe. Conflict Studies Research Centre, Central & Eastern Europe Series 04, pp. 9-10.

Schlesinger, J. R. (1973). Military Service Predilections. National Defense University. Retrieved April 22, 2008 from: http://www.ndu.edu/inss/Books/Books_1998/Military%20Geography%20March%2098/milgeoch14.html

Security, Globalization, and Mass Society into the Global Information and Terrorism Age. (October 28, 2006). The Transnistria Republic and Arms Exports to the Middle East. Retrieved April 22, 2008, from http://www.bogdan-george-radulescu.ro/librarie/transnistria_arms_exports_middle_east.pdf

Serebrian, Oleg. (2004). Politica si geopolitica, [Politics and Geopolitics]. Cartier. Chisinau, p. 24.

Solana urges Moldova to more active reforms (2008, April 16). Moldova Azi. Retrieved April 22, 2008 from: http://www.azi.md/news?ID=48981

Stefan Wagstyl (July 10, 2007) Politics preserves Moldova’s divide. The Financial Times. Retrieved April 22, 2008 from: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/dada9b6e-2efc-11dc-b9b7-0000779fd2ac.html

Story from BBC NEWS. (March 12, 2008). BBC NEWS. Retrieved April 22, 2008, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/1/hi/world/europe/country_profiles/3641826.stm

The Failed States Index 2007. The Rankings. Foreign Policy. Retrieved April 22, 2008 from: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=3865&page=7

The United States and the Transnistrian Conflict (July, 2005). Retrieved April 20, 2008 from U.S. Department of State (USDS) web site: http://www.state.gov/p/eur/rls/fs/53741.htm

Ukraine’s Future and U.S. Interests. (May, 2004) United States Department of State. Retrieved April 22, 2008, from http://www.state.gov/p/eur/rls/rm/32416.htm

US House of Representatives proposes forgiving Moldova’s foreign debt (April 18, 2008). Moldova Azi. Retrieved April 22, 2008. from: http://www.azi.md/news?ID=49020